Danzas fronterizas : Contemporary dance experiences in the Tijuana-San Diego region

While I wait to cross the border from Tijuana, Mexico to San Diego California, I have ample time to think about my day, hear music and observe immigration agents guiding contraband-sniffing dogs around crossing cars, in stark contrast to the stray dogs that weave in and out among the vehicles. I see pharmacies and huge billboards illuminated twenty-four hours a day announcing quinceañera1 dresses, Mexican and American phone services, and even plastic surgeons. I smell and see emissions escaping through exhaust pipes of cars, Mexican venders of magazines, bottled water, and blankets; old and new regulations in English and Spanish; plaster figurines of Disney characters; children, women, and older men selling chewing gum and asking for handouts.

In this space, while surveillance cameras seem to multiply every day, I hear a globalization of sounds: sounds of construction, a multiplicity of voices, and music of diverse tastes. The San Ysidro Port of Entry is a visually and aurally noise-filled space2. But most of all I see the people who, like me, sit in their cars waiting to cross the border to “el otro lado.”3 Although the complexity of this border space makes it difficult to describe, my waits to cross have allowed me to observe the regular activities and physical transformations, and ongoing changes at this site. In this space, purportedly an area of safety, many people have had jolting experiences, such as hearing gunshots or seeing U.S. officials suddenly take unsuspecting passengers from their cars in handcuffs. It is a dichotomous paradox: to this paradox in terms of safety could be added yet another, in terms of mobility: the border implies a stop of flow, a stop of movement yet at the same time it is where people and things are in constant movement, moving slowly but always forward to cross the border. Here, thousands of us are present together; we undergo different experiences that leave a ghostly trail.

As someone who grew up in the borderlands, and as a choreographer who regularly crosses the border to work with other border-crossing dancers, I use biographic and ethnographic approaches to examine how our borderland experiences shape our work as dance-makers. I write from and about the border, as an artist/scholar haunted by border-crossing occurrences and who reflects on the impact of our vivencias fronterizas (border experiences) in the making of concert contemporary dance4.

In the 1990s, choreographers started to create, what I call Danzas fronterizas (border dances), testimonies and reflections of the experiences of those affected by the borderland, whether allowed to cross the border or not. These choreographies addressed the social, economic, and political problems affecting the area, such as racism, immigration, narco-trafficking, and smuggling. These activities have enabled and hindered the emergence of choreographers and dancers on both sides of the border as well as communications between us. I examine how border activities and conflicts have been thematized in choreographic works, contributing to the establishment of a unique culture, which I understand as border dance culture/cultura de la danza fronteriza.

As long as I can remember, I have been a regular border crosser at this gate. At a very early age, I learned to take note of the time spent, wasted, endured, and lost at the San Ysidro Port of Entry. Every decision I make must also consider the time it takes to cross the border. I have been curious about what people do during the long waits, the portions of our lives spent waiting at the border, how each of us practices this journey, the imprints that border crossings leave on our bodies, and our perceptions of this border.

I used the time in line to reflect on what it means to “live the border” and created a dance piece related to this space. The realization that while I am sitting in my car, waiting to cross, other people are dying in their attempts to move across is disturbing, uncanny. As I cross through the expedited SENTRI5 lanes, I reflect on the disparity, painful contrast and inequality of this space. Inequality here is founded historically in the building of a fence between the two countries. In the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe in 18486, the United States gained a huge portion of Mexican territory, and a new borderline was drawn. Populations along the redrawn border perceive the resulting inequalities in various ways7.

The most dramatic inequalities begin with the rules governing those allowed and those unfit to cross. Border scholars have stressed that the meaning of the border fence is tightly linked to these various forms of inequality. In Gloria Anzaldúa’s words, borders “are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them.”8. Ramón H. Rivera-Servera and Harvey Young add that depending on where one resides, “it is to be domestic or foreign, home or abroad, insider or outsider, citizen or immigrant, at rest or on the move.”9 And José Manuel Valenzuela Arce, writing from the Southern side of the border, states that “to speak from the border is to place oneself within a context that denies centrality, given that border equates with periphery. A border line is the beginning and the end, rupture and continuity.”10 As a choreographer, living on both sides of the border, I am motivated to uncover these current-day inequalities and turn them into movement—something that the process of choreography allows me to do11.

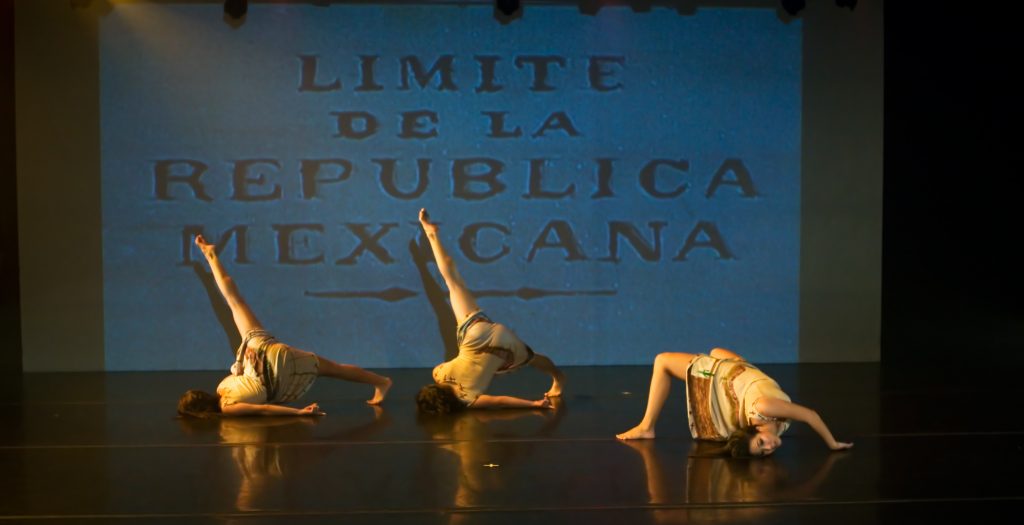

I started to work in Danzas fronterizas in 1995 with a group of dancers from both sides of the border, who have been gathering in Tijuana for rehearsals and events for eighteen years. In this essay, I examine two Danzas fronterizas: Danza indocumentada (undocumented dance, 2005) and Globótica (2010). Prior to beginning to choreograph Danza indocumentada, the images of people on the Mexican side looking toward the North as they waited for a chance to cross, resonated in my imagination as I myself was crossing the border. Waiting safely in my car I imagined these people who risked their lives in order to cross. I looked at my passport and drew a connection between this document and the deaths of thousands of people who did not have one. This led me to contemplate how documents encapsulated power and how I could transport and translate this reflection about opportunity and death into choreography.

Danza indocumentada is my attempt to re-humanize border-crossers robbed of their very personhood by economic, political, and/ or racist forces. The dance starts with two women, and three men, who are in front of a painting by Roberto Rosique12. The painting shows two individuals sitting beside the border fence, a third is in the process of climbing the fence, while the fourth sits with his back to the viewer. On the U.S.-side (the North side), we see the Statue of Liberty and a sign that warns “Don’t Cross.” The dancers’ first movements are derived from images I routinely witnessed along the border. On one occasion, I spoke with one of the would-be crossers and asked him why he placed his hand on his forehead while laying down to rest. He responded that he did so to block the sun but also to hide the fact that he was asleep. By pretending to be awake, he could “keep watch” for anyone trying to steal his belongings. The dancers emerge from the poses and through a combination of contemporary dance movements and steps drawn from folk dances of Northern Mexico, tell a story about the stresses born out of fear and desire, the perceptions and dreams that every migrant holds every migrant. I wish to show the corporeal positions, hunting gazes, gestures denoting furtive conditions, fears, and vulnerabilities, while at the same time addressing border crossers’ hopefulness—the thrust that leads them to cross the border.

In Globótica I wanted to make reference to aspects of globalization and to disturbing, yet humorous, situations along the border. This piece references the effects of the influenza A virus (H1N1) in Mexico in 2009. My inspiration came when the Mexican government declared that all Mexicans should wear masks to control the spread of the epidemic, so people in Tijuana had to wear masks, but not those in San Diego. While most public activities were canceled in Tijuana because of health concerns, this was not true in San Diego, and many people crossed the border to attend shows and events in the United States. The situation at the border was bizarre: people wearing masks in Tijuana shed them as soon as they crossed the border. This experience highlights the incongruity of border politics, where a region is cut in two.

For this piece I asked Mexican border poet Estela Alicia López Lomas to create a text for the movement, which a solo dancer delivers on stage. Standing up center right, the dancer reads the following: “…I e-mail the world, and the cold-bug answers: I am the future of dreams…(Sneezes) –Excuse me. Come, dream a dream with me! I am a Maquila Girl, Tijuana Girl, dreaming….” The dancer moves to center stage and looks directly at the audience with a wry face, almost a smile. Silently, she begins to move her body in an undulating motion, challenging the audience with an expression that could be read as projecting security, sarcasm, and authority.

The music begins as she extends her body and limbs, in various directions while glancing over the space. The contemporary music accompaniment shows the influence of the tango, a globalized music and dance13, which serves as a background for conveying “globalization” as border experience. The dancer returns to center stage, where her movements evoke the fusion of Asian and American dances. She shifts abruptly from side to side, where a light now divides the stage. She appears to enter into conversation with someone, but is actually in conversation with herself. Her stooped body and hand moves suggest money counting. She moves from one side of the stage to the other several times, as if to see the wake she creates. Sitting down, she extends her arms like tentacles, collecting fruit from various points. She devours a piece in hungry bites. She switches into dancing a Northern Mexican step that is associated with pride, character and determination, and is traditionally used to mark the end of the dance. The piece finishes when the dancer’s eyes attempt to lock onto the audience.

In Danza indocumentada and Globótica I attempt to capture slices of what is shaping border dance culture. These Danzas fronterizas focus on my personal experiences involved with crossing the border and with the loss of thousands of lives as they attempt to cross the U.S.-Mexican border. In the process of choreographing and writing about border experiences I have noticed how both forms of analyzing the theme of the dance has its own contributions to explain the border phenomena. In dance, I perceive that using movement analysis allows a different reading of the problem, for example when I ask the migrant “why he placed his hand on his forehead” I learned that the reading of his movement opened up the possibility for me to know about other aspects of his life at the border, as in how to survive in this place—the thoughts are read throughout his body language.

As a dance-maker and recently as an academic, border studies have also influenced my choreographic process. I reflect on the multiple views about the border from other scholars. Now both dance and border studies intertwine and complement my approach to create Danzas fronterizas. Before entering academia, what I did came directly from what I saw at the border and my own perspective of the problem. The tools of dance and border studies allow me to see not only “my border” but also others’.

Notes

1.Girls celebrating their fifteenth birthday, a kind of “coming of age” affair in Mexico.↩

2.The San Ysidro Port of Entry, where currently more than 40 million people cross the border each year, making it the busiest land border in the world.↩

3.People in Tijuana refer to the crossing as “ir al otro lado”—to go to the other side of the border. ↩

4.Other contemporary choreographers who have created at least one Danza fronteriza: Patricia Rincon, Jean Isaacs, Allyson Green, Jaciel Neri, Henry Torres and Ángel Arámbura.↩

5.The SENTRI (Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection) program, launched by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, incorporates dedicated commuter lanes where prescreened applicants and vehicles are allowed to cross the border northbound into the United States, usually more quickly and efficiently.↩

6.Rachel St. John. Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2011, 14.↩

7.Border related differences have become so routine that border residents barely notice them, including Spanish-English language switching and dollar-peso currency conversions.↩

8.Gloria Anzaldúa. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 2007, 25. ↩

9.Ramón H. Rivera-Servera and Harvey Young. Performance in the Borderlands. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 1.↩

10.José Manuel Valenzuela Arce. Nosotros: Arte, cultura e identidad en la frontera México-Estados Unidos. México, D.F.: Culturas Populares de México. Conaculta, 2012, 78. My translation. ↩

11.The wait in the borderline also forms part of my choreographic process, because this is where I find elements of my work. ↩

12.Roberto Rosique is a plastic border artist that lives and works in Tijuana.↩

13.See Marta E. Savigliano. Tango and the Political Economy of Passion: Structures of Feeling. Boulder: Westview Press, 1995.

↩

Minerva Tapia

Conversations across the field of Dance Studies

Society of Dance History Scholars

2014 Volume XXXIV